(and adjacent areas)

- Geology

- Arrival of first humans

- Coming of Euro-Americans

- First settlers

- Development of Sellwood

- Oaks Bottom as the Slough

- Acquisition by the City of Portland

- Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge

- The 21st century

35 million years B.P.: The north-south alignment of the Willamette Valley is created as a forearc basin induced by plate tectonic interaction between the Farallon and North American plates. This basin is originally part of the continental shelf. (Most of the Farallon Plate becomes subsumed over time, with the current Juan de Fuca Plate one of the remnants.)

20-16 million years B.P.: The Coast Range is uplifted to separate the basin from the Pacific Ocean. In Portland, an ancestral river runs its course along the broad syncline, with the anticline the emerging West Hills.

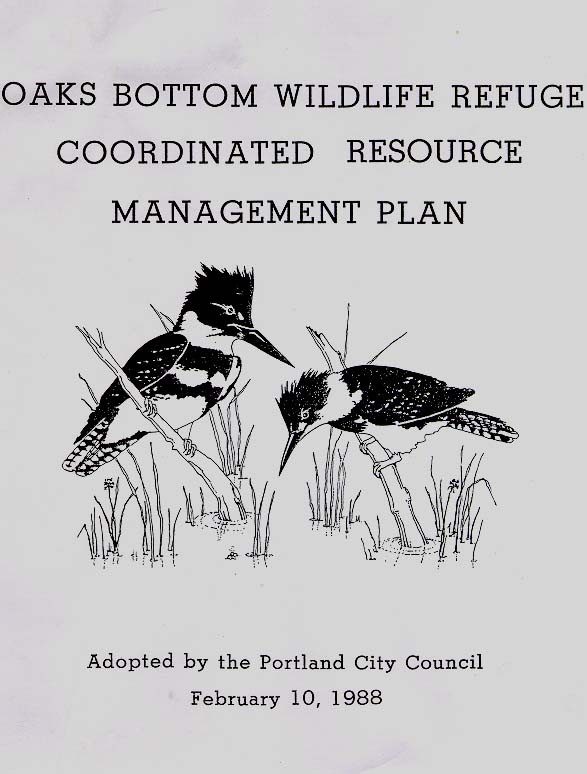

Courtesy: U.S. Geological Survey

16-15 million years B.P.: Flood basalts from eruptions in what is now eastern Oregon bury much of the area. Subsequently, the courses of the Columbia, Willamette, and other rivers cover these basalts with thick deposits of sediments.

3.5 million years B.P.: Lava from numerous vents in the Cascade Range flows into the Portland Basin.

1.8 million years-575,000 years B.P.: Lava flows from numerous local cinder cones and vents, as well as three shield volcanoes, are emitted throughout the Portland Basin. This is the active period of the Boring Lava Field within the basin.

18,000 years B.P.: Terrace deposits, probably from glacial outwash fans, are the next significant layer of material to appear in the Portland Basin. (The basin itself was never glaciated.)

15,500-13,000 years B.P.: A series of massive floods, known as the Bretz, Missoula, or Ice Age floods, discharges from a huge glacial lake in Montana and rushes down the route of the Columbia, backwashing up the Willamette, with the Portland area briefly under up to 450 feet of water each time. Flood deposits up to 120 feet deep settle on the valley floor during the temporary lives of what geologists call Lake Allison. Over time the Willamette River carves its course through these gravely deposits, creating the sweeping bend at Oaks Bottom.

13,000 years B.P.: After the last glacial period, sea levels gradually begin to rise. Before this, the lower Willamette paleochannel was about 250 feet below where it is now

10,000 years B.P.: Humans arrive in the lower Willamette Valley. By the time Euro-American fur traders and settlers arrive, the main groups on the Columbia and lower Willamette are bands of the Chinook (or Kiksht), with the Multnomah based on Sauvie Island. The Clowwewalla and Clackamas bands are based farther upstream on the Willamette although all three groups forage and hunt the basin. The area of Oaks Bottom, for example, hosted an abundance of wapato (Sagittaria latifolia) and camas (Camassia quamash), staple foods harvested by all three bands.

1806: Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition enters the Willamette River. He is guided by local “Cash-hooks” (Clackamas), who tell him they call the river Mult-no-mah. Clark estimates the population of the Portland Basin to be 5,000 to 11,000. On his way back to the Columbia, Clark arrives at a village where the population has been decimated by smallpox.

1812: Alfred Seton and William Henry of the Pacific Fur Company paddle past Oaks Bottom to portage around Willamette Falls and establish a trading post at the location of Champoeg.

[he wasn’t]

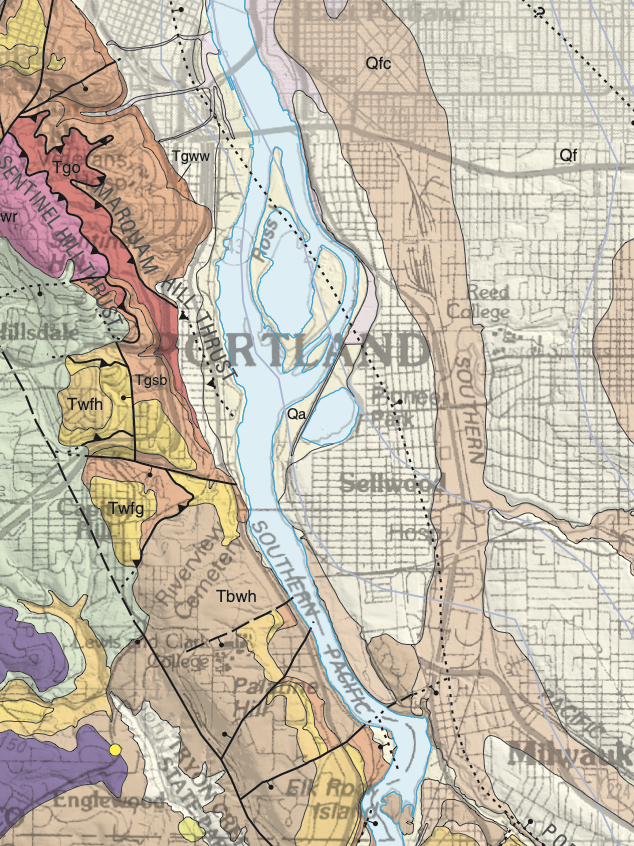

Oregon Historical Society Research Library,

Call No. 021395

1826: Scottish botanist David Douglas visits the general area and documents the plant life. He reports a terrible fever (malaria) which has afflicted tribal populations at a 90% mortality rate.

1836: Settlers using the Oregon Trail begin a migration that becomes a flood in 1843. Early settlements like Champoeg and Oregon City begin to develop.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library OrHi 61321 & bb004274

1838: Father François Norbert Blanchet, a Catholic priest appointed the first vicar general of the Oregon mission, arrives in the Willamette Valley. Blanchet writes the first specific accounts of native groups along the Willamette. In his writings, he also mentions a “Wapato Lake”, probably Oaks Bottom, which he states was a major stopping point for Indians traveling the river.

1841: Lt. Charles Wilkes of the U.S. Exploring Expedition reaches the Willamette. He records only 575 Chinook survivors of the malaria epidemic.

Mid-1840s: Milwaukie Road (now Milwaukie Avenue) is laid out by Benjamin Stark and Francis William Pettygrove as a wagon road to connect Portland with Oregon City.

1847: The first Euro-American settlers arrive in the Sellwood area.

1850-1872: Oregon Donation Land Claims are surveyed. Claims covering the current Oaks Bottom wildlife refuge include (from north to south) those of Gideon Tibbetts (Claim 64), Edward Long (Claim 56), Alfred Llewellyn (Claim 49), and Henderson Llewellyn (Claim 51). (The Llewellyns later change the spelling of their name to Luelling.)

1882: Henry Pittock’s Sellwood Real Estate Company purchases over 300 acres for $32,000 from the Rev. John Sellwood and files for a new development.

1887: The City of Sellwood is incorporated. There are about 100 homes, three stores, a church, and a school.

1893: The East Side Railway Company (later the Oregon Water Power & Railway Company (OWP & R Co.), the Portland Traction Company, and PEPCO) builds a line along the east bank of the Willamette between Portland and Oregon City to become the country’s first electric interurban railway. A high embankment, eventually 30 yards in width, crosses the wetland at Oaks Bottom (then known simply as the Slough), effectively sealing the area off from the annual floods that flushed and replenished the wetlands.

1893: Sellwood becomes part of Portland.

1894: Portland’s greatest flood raises the Willamette River 33.5 feet and puts the Slough (Oaks Bottom) completely underwater.

Oaks Bottom/Ross Island area

1901: The City View Race Track (now Sellwood Park), where locals could “exercise” their horses, is considered as one of the sites for the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition. (The location eventually chosen is at Guild’s Lake in northwest Portland, which is drained to accommodate construction.)

1905: Oaks Amusement Park, created on fill, opens two days before the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition. This is the “brainchild” of Fred Morris, president of the OWP & R Co., which cashes in by running world’s fair attendees by trolley to the amusement park.

1906: The Sellwood Bee, founded by Charles Ballard and C. T. Price, publishes its first issue on 6th October.

c1907: The Oregon Yacht Club moorage is developed just north of Oaks Amusement Park. This later becomes mostly a gated community of floating homes.

1909: The City View Race Track becomes Sellwood Park. In 1910, the first public park swimming pool in Portland is opened there.

1910s-1940s: According to Evangeline Nyden, young Sellwoodites would gather on the Slough Bank (top of the bluff) and watch the fireworks displays and “balloon ascensions” at Oaks Amusement Park. The Slough was usually 2 – 10 feet deep in water, and a steep pathway connected to the electric trolley tracks. The bluff was “wild and uncleared,” an “enchanting garden” with “bushes of red currant blooms coaxing the hummingbirds.” Hundreds of ducks and other waterfowl used the Slough to the tune of the “noisy sucking sounds of carp.”

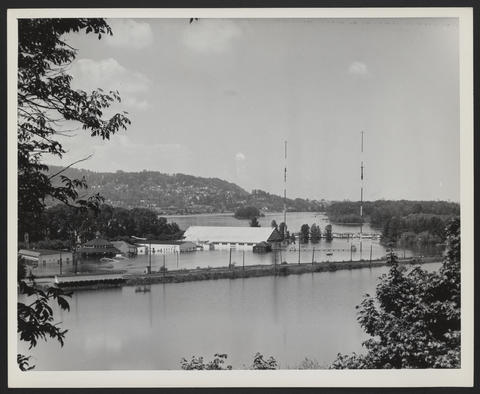

Oregon Historical Society Research Library OrgLot151_PGE133-2

Oregon Historical Society Research Library OrgLot762_B1F8_028

1920s-1970s: The Slough (Oaks Bottom) is seen by many as a project for urban development, a fetid eyesore, a dumping ground for personal trash, a mosquito breeding ground, a noisy venue for dirt bikers, and/or a tangle of vegetation concealing unknown dangers.

1943: The Portland Electric Power Company, owner of the OWP & R Co,, sells Oaks Park to the Edward Bollinger family.

1948: The Vanport Flood keeps Oaks Bottom and Oaks Amusement Park underwater for a month.

1957: A committee considers using the Oaks Bottom area for an outdoor railroad museum.

1958: The interurban railroad, which served Oaks Amusement Park, is abandoned.

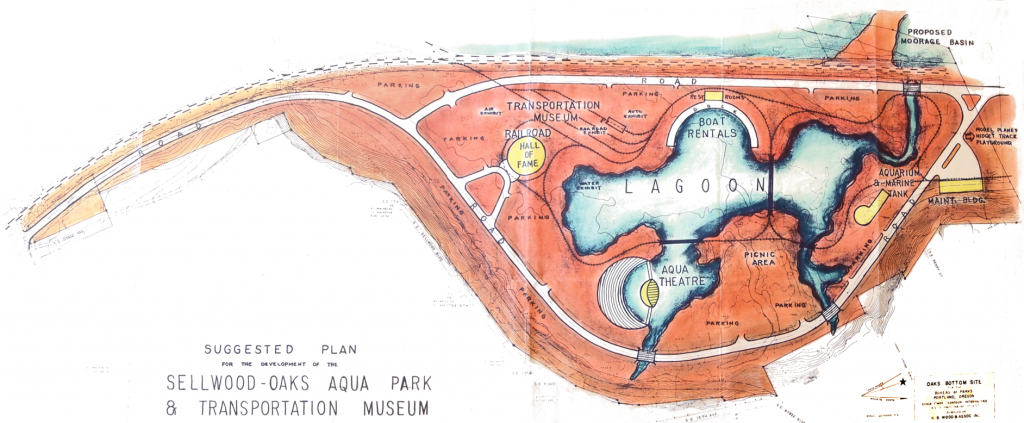

1959: The City of Portland acquires most of what is now the Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge (115 acres) in a land swap with PGE. The city council names it “Oaks Pioneer Park.” Commissioner Ormond R. Bean advances a 13-point program for development of the site, including a transportation museum, reproductions of historical buildings and pioneer towns, exhibits about lumbering, farming, and fishing, and “aquatic recreation facilities.”

Courtesy: Portland Parks

1960: Harry Buckley, superintendent over the new park, announces that $200,000 will be needed just to fill in the area to the 25-foot level, a price tag that gives pause to development plans. Norbert Leupold, president of the Audubon Society of Portland (now the Bird Alliance of Oregon), argues for protection of the wildlife, citing one of the last riparian woodlands in Portland, the value of a wintering area for waterfowl, and the presence of a beaver family and dam.

Early 1960s: The City allows the southern end of Oaks Bottom to be used as a “smoldering garbage heap.” The area, previously a wetland and now the South Meadow, becomes buried to a depth of 10-15 feet with rubble and other garbage. The plan is then to convert it to a parking area.

1963: Al Miller of the Audubon Society of Portland and Oregon Journal outdoors writer Tom McAllister argue on behalf of the Nature Conservancy that the area should be named Wapato Marsh Wildlife Refuge.

1963: Construction of the Stadium Freeway (I-405) begins as over a thousand houses and businesses are demolished. The north 47 acres of Oaks Bottom, owned by the Donald M. Drake Company, becomes a 20-foot deep repository of demolition rubble. This fill and the south fill bury much of Oaks Bottom’s wapato habitat.

1964: The Christmas Flood completely submerges the Bottom (as well as Willamette Falls and the lower deck of the Steel Bridge). It brings “water to the ears of the animals” in the carousel at Oaks Amusement Park.

Late 1960s: The city promotes another plan for development at Oaks Bottom. This includes a site for a Children’s Museum, a “lagoon” with boat rentals, and a motorcycle track. Several groups oppose the plan and instead advocate for a wildlife refuge. These groups include the Audubon Society of Portland, The Nature Conservancy, the Sierra Club, and the Sellwood-Moreland Improvement League (SMILE).

Photo: John Sparks

1968: A steep, 1,400-foot switchbacked trail down the bluff from Henry Street is constructed, giving access to the Bottom as an “outdoor classroom” for Llewellyn Elementary School students.

1968: Under Parks Commissioner Frank Ivancie, the city exercises an option to purchase, for $807,000, the Drake property under the greenway program. (Previously, local philanthropists John Gray and Mary Beth Collins had purchased the property in order to ensure its protection.)

Early 1970s: The Youth Conservation Crew (YCC) builds a two-mile loop trail at Oaks Bottom.

1972: SMILE asks Portland State University’s Urban Planning Department to produce plans for the Bottom, the so-called Ritchie Report. The students advance four different plans. The preferred plan is a refuge in the center of the property, with other kinds of development on the two landfills. Al Miller and others at Audubon insist that the entire area of the Bottom become a refuge.

1973: The Oregonian runs an article on April 23rd about Audubon’s vision for Oaks Bottom and interviews Al Miller.

Mid-1970s: Diana Cvitanovich and other PSU students produce the documentary Riparian about the history of Oaks Bottom. The film can still be seen on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gQgrq9qf3Ck

1979: David Anderson’s A Field Guide to Oaks Bottom is published by the Audubon Society of Portland.

1979: The City of Portland develops a Willamette Greenway Plan.

1980: Under the auspices of SMILE and Audubon, Mike Houck and Martha Gannett start the Bottom Watchers. The group does cleanups and trail maintenance. Martha Gannett designs the iconic Bottom Watchers T-shirt. Gay Greger, volunteer coordinator for Portland Parks, lends some support.

1980s: Portland Parks and Recreation (PP&R) begins to take a greater interest in natural areas under the leadership of Portland City Commissioner Mike Lindberg. Parks staff members Jim Sjulin, Steve Bricker, and Fred Nielsen focus on the management of natural areas.

1984: Mike Houck, then the urban naturalist for the Audubon Society of Portland, and Jimbo Beckman post 40 bright yellow ‘Wildlife Refuge’ signs around the Bottom. After this, local media begin to refer to the area as the Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge.

1986: The City Club agrees with Audubon that the entire area, including the landfills, should be managed as a wildlife refuge.

Photo: Mike Houck

Photo: Robert Liberty

1986: Mike Houck successfully campaigns to have the great blue heron designated Portland’s official bird. He wins the support of Mayor Bud Clark.

Late 1980s: A large water main, five feet in diameter and built to convey potable water from the Powell Butte reservoir to the west side of Portland, is extended across the south landfill (now the South Meadow).

1987: Dale Pritchard, general manager of Oaks Amusement Park, announces a $20 million renovation.

1988: In response to neighborhood complaints about mosquitoes, Peter DeChant, of Multnomah County Vector Control, applies for a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to completely drain Oaks Bottom. Mike Houck, Jim Sjulin, and others decide a better idea would be to install a weir on the outlet creek to keep water at a constant level and allow for vegetation management.

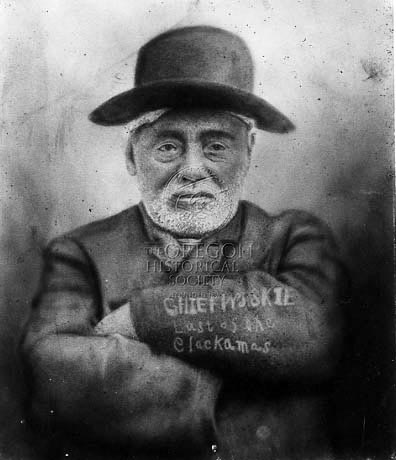

1988: The Portland City Council establishes Oaks Bottom as the city’s first official “urban wildlife refuge” and approves the Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge Coordinated Resource Management Plan, authored by Audubon’s Mike Houck in collaboration with Peggy Olds of the East Multnomah County Soil & Water Conservation District and wetland ecologist Ralph Thomas Rogers.

1989: A registered “domestic nonprofit corporation” called the Friends of Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge, with Robin Shepard as President and Martha Taylor as Secretary, is born.

1991: Mike Houck contracts with ArtFX muralist Mark Bennett to paint a fifty-foot-high great blue heron on the Portland Memorial Mausoleum above Oaks Bottom. Bennett uses medical illustrator Lynn Kitagawa’s heron watercolor as a basis for the mural.

1993: The East Portland Traction Company begins running its excursion trains on the remaining railroad track. This service has now stopped, but the Oregon Pacific Railroad continues to host special excursions on the track.

Mid-1990s: A second iteration of the Friends of Oaks Bottom, under Maryann Schmidt, succeeds the previous group, which had become dormant by 1994.

1995: Mark G. Wilson, a local ecologist, coordinates the planting of native shrubs, wildflowers and grasses in the North and South meadows in partnership with Dick Pugh and Cleveland High School biology students as well as Friends of Oaks Bottom and PP&R volunteers. They plant over 9,000 trees and forbs.

1996: The Willamette Valley Flood completely inundates the Bottom.

1996: A permit is filed to improve the steep trail down from Henry Street that facilitates access for school groups. Jim Sjulin, Portland Parks’ natural resources supervisor, enlists the aid of Geotechnical Resources, Inc. to assess the feasibility of improvements. A project was never approved, and the trail has gradually disappeared into the bluff.

1998: The City of Portland’s Sellwood-Moreland Neighborhood Plan includes protecting Oaks Bottom as a green space and wildlife refuge.

1999: James Allison, of Friends of Trees, and Mark Wilson use a grant from the city to establish a third iteration of the Friends of Oaks Bottom.

2000: The Portland City Council establishes funding to hire the first PP & R ecologists, stewardship coordinators, and a natural resource planner. Mark Wilson is hired as the River Ecologist to manage PP&R lands in the mainstream Willamette River watershed. Wilson works with Darian Santner, of the City’s Bureau of Environmental Services revegetation team to remove invasive species in Oaks Bottom, such as Himalayan blackberry, and replant native species.

2000: A catastrophic wildfire burns on City of Portland and adjacent University of Portland lands along the north bluff at Mocks Crest. The event prompts the formation of a multi-bureau response focused on wildfire risk reduction throughout Portland. Lessons learned would be applied to subsequent work at Oaks Bottom.

leading a tour at the Bottom

Photo: Mike Houck

2001: The PP & R Natural Resource Program becomes PP&R City Nature and initiates an ecosystem management planning process for Portland’s natural area parks modeled on The Nature Conservancy’s land management planning.

2001: Jim Desmond, open spaces acquisition manager for Metro, announces the purchase of a three-mile right of way after 50 “difficult” meetings with Dick Samuel of the Oregon Pacific Railroad. The cost is $845,000, part of the 1995 $135 million bond measure. This will become the stretch of the Springwater Corridor next to Oaks Bottom.

Photo: Darian Santner

2003: Mark Wilson recruits Portland State University capstone students to conduct a GPS survey to map all existing Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana) on the Oaks Bottom bluff.

2004: Bob Sallinger, conservation director at the Audubon Society of Portland, successfully secures the Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge as Portland’s first Important Bird Area (IBA) and migratory bird park.

2004: In response to Multnomah County Vector Control’s concerns about West Nile virus, the application of the pesticide Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) is made to the refuge’s wetlands and open water areas to control mosquitoes. The previously installed weir had not been successful in controlling all species of mosquitoes.

2004: Again, very high waters of the Willamette River completely inundate Oaks Bottom’s wetlands and riparian woodlands. More than 30 landslides are identified along the Oaks Bottom bluff. Several stormwater gabions are constructed along Sellwood Boulevard. A City Landslide Group is formed to prescribe slope stabilization projects.

2005: The section of the Springwater Corridor that runs along Oaks Bottom, the original interurban line, is completed.

2005: Portland Parks completes its Ecosystem Management Plan for Oaks Bottom.

Photo: John Sparks

2006: Mark Wilson (PP&R), using amphibian survey data collected by Reed College and PSU biology students, obtains an OWEB grant to enhance amphibian habitat in the North Meadow area. Using nearby emergent wetlands as a reference, shallow ephemeral breeding ponds for two frog species and four salamander species are constructed by removing fill soils and construction rubble. One of these ponds, Tadpole Pond, is accessible to the public.

2007-09: Mark Wilson (PP&R), in partnership with staff from Portland’s Environmental Services (BES), Fire and Rescue (PF&R), and Planning (BPS) obtains a three-year FEMA grant to begin wildfire fuel reduction work on private/public lands in/around four PP&R natural area parks (Forest Park, Oaks Bottom Bluff, Mocks Crest Bluff, and Powell Butte.) The grant also funds the development of ecological burn plans and staff training in prescriptive burning for fuel reduction and habitat restoration. Two prescriptive burns each in the South and North meadows are implemented, and there is extensive clearing of invasive clematis, blackberry, and other flammable ladder fuels on the Oaks Bottom bluff from its north end south to Sellwood Park.

2007: ArtFX’s Mark Bennett contacts Mike Houck to continue work on the mausoleum mural. Mark, son Shane, and artist Dan Cohen paint seven additional walls of the mausoleum, creating a 55,000-ft mural, the largest hand painted building mural in the country. Houck, now Director of the Urban Greenspaces Institute, gets permission from the Regional Arts and Culture Council (RACC) and raises $75,000 to fund the mural. The mural is dedicated in 2009.

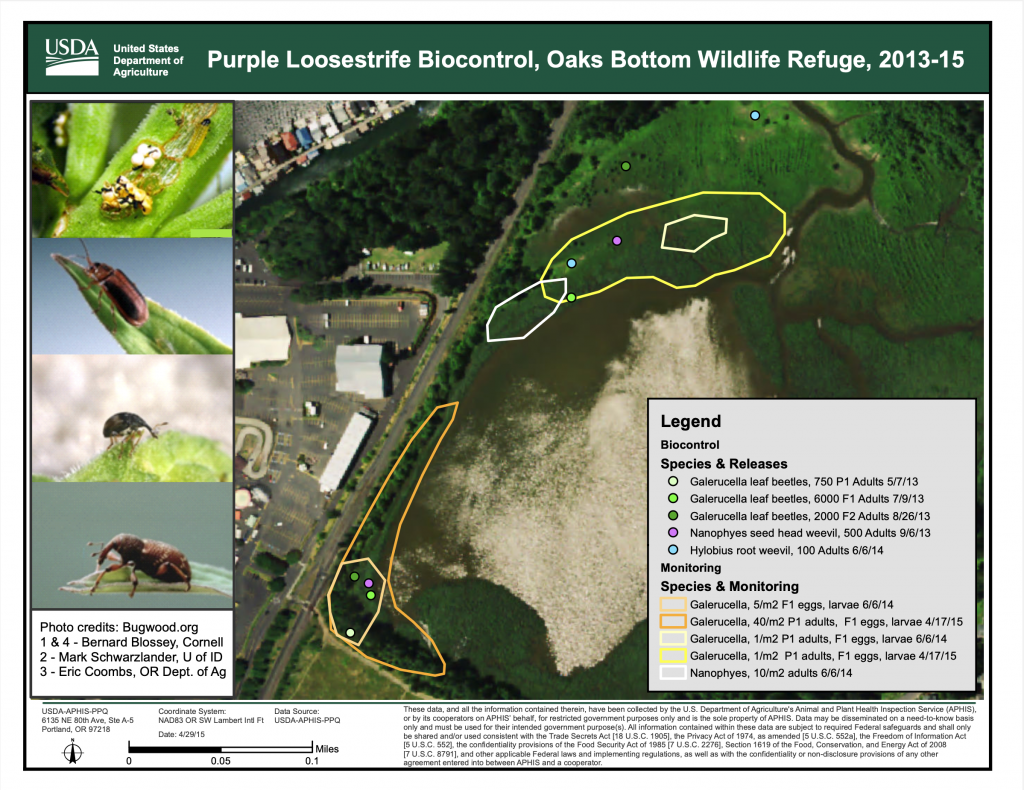

2008: PP&R’s Mark Wilson, in consultation with Marc Peters of the Bureau of Environmental Services, enlists the services of the USDA Animal Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), and the Oregon Department of Agriculture (ODA), to release three species of beetles as a biocontrol agent to reduce the flourishing population of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria). However, the natural hydrology of the Bottom is still affected by the use of the weir, so the beetles are not able to do their job. Releases of these biocontrol agents continued for several more years through 2014 in hopes the beetle population would increase and have an impact on the purple loosestrife.

Photo: John Sparks

2012: The Bluff Trail and the Sellwood Park Access Trail are refurbished by Twin Oaks Construction, with a new all-season tread and a set of boardwalks, viewing platforms, and bridges.

2013: SMILE’s Stewardship of Natural Amenities Committee (SNAC) begins developing a vision and establishing native plantings at a small area owned/managed by Portland Transportation (PBOT) at the top of the bluff at a place called Oaks Bottom Overlook on 13th and Bybee.

2015: During the summer of 2015, water levels at Oaks Bottom are quite favorable for the leaf-eating biocontrol agents for purple loosestrife – Galerucella calmariensis/G. pusilla. In addition, the huge population of the host plant on site combined with a long and successful active growing season for the beetles created the perfect storm. As a result, the populations of these beetles soared mid-summer and decimated the loosestrife in Oaks Bottom. An unfortunate side effect is the beetles moving to private gardens adjacent to the refuge. Fortunately, it was a temporary nuisance that subsided in a week.

2018: Under the Oaks Bottom Habitat Enhancement Project, overseen by Portland Parks, BES, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the culvert that carries the Bottom’s creek to the Willamette is replaced by a much bigger box culvert. The seasonal weir is taken out and surrounding wetlands are planted with native trees and shrubs. River mussels are seeded in the creek. In addition, it is hoped that migrating salmon will now use the creek and marshes as resting places. In addition, the Galerucella beetles appear to have gotten control over the purple loosestrife. High water levels in the spring may also contribute to the demise of the loosestrife.

2019: A beaver family constructs a dam where the outlet creek exits Wapato Marsh, thus ensuring constant water levels throughout the year. This stymies the plan that low water levels in the summer would attract foraging shorebirds to exposed mudflats.

area at Wapato Marsh Photos: Marc Peters

2020: Ezra Cohen and Joshua Meyers present their plans to revive the Friends of Oaks Bottom at a SMILE meeting. They also hold their first work party at the Bottom.

2022: Friends of Oaks Bottom testifies with SMILE before the city council to oppose the rezoning of a parcel on Milwaukie Avenue in order to allow a 75-foot-tall apartment building on the bluff above the wildlife refuge. However, the City Council decides to allow the rezoning and the project to go ahead although, as of 2025, construction had not begun.

2025: The beaver dam falls apart and water levels in Wapato Marsh drop 2-3 feet. Two beaver carcasses are found, the deaths maybe caused by a territorial conflict. The exposed rim of flats is quickly revegetated by purple loosestrife and other plants, mostly non-native. A second beaver dam on the creek means there is no summer drawdown. The creek dam is actively being maintained, perhaps by a beaver family new to the area.

2025: Along with the Bird Alliance of Oregon (formerly Audubon), Friends of Oaks Bottom opposes construction plans for a 147-foot lighted drop tower in Oaks Amusement Park, and suggests several modifications friendly to wildlife. Unfortunately, the City does not approve these modifications.

2025: PP&R publishes its natural area plan for dealing with the coming emerald ash borer (EAB) crisis. Selected ash trees will be saved via inoculation, while the City will begin a program of underplanting in the ash groves of Oaks Bottom and other natural areas. Friends of Oaks Bottom assists with the first such underplanting project in December 2025.

Photo: John Sparks

Photo: Andrew Cohen

Sources:

Anderson, David P. A Field Guide to Oaks Bottom. Portland: Audubon Society of Portland, 1979.

Ashton, David F. “Restoration project nears completion on Oaks Bottom’s Bluff Trail.” The Bee (November 1 2012), https://thebeenews.com/2012/11/01/restoration-project-nears-completion-on-oaks-bottoms-bluff-trail/

Bass, Craig. “Portland Traction Company, Back in the Day.” Craig’s Railroad Pages (1981), https://www.craigsrailroadpages.com/ptc-back-in-the-day.html

Burns, Adam. “Portland Traction Company (PEPCO): Serving Portland’s Suburbs.” American Rails (last updated 10 September 2024), https://www.american-rails.com/pepco.html

“City Names Park Area.” The Oregonian (25 December 1959).

City of Portland Bureau of Planning. “Sellwood-Moreland Neighborhood Plan”, April 1998. https://sellwood.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Sellwood-Moreland-Neighborhood-Plan.pdf

Cvitanovich, Diana. Riparian. Portland: BlashfieldStudio, c1975. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gQgrq9qf3Ck

Decker, Doug. “The Oaks plans 10-year, $20 million renovation.” The Bee (January 15 1987).

Evarts, Russell C., Jim E. O’Conner, Ray E. Wells, Ian P. Madin. “The Portland Basin: A (big) river runs through it.” Geological Society of America (September 2009), https://rock.geosociety.org/net/gsatoday/archive/19/9/article/i1052-5173-19-9-4.htm

Fitzsimons, Eileen G. “Historic Sellwood.” SMILE, https://sellwood.org/history/

Fitzsimons, Eileen G. Email exchanges, November 2025.

Gandy, Shawna. “François Blanchet (1795-1883).” The Oregon Encyclopedia (last updated 23 Jan. 2020), https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/blanchet_francois_1795_1883_/

Guderyahn, Laura. “Why Is the Oaks Bottom Reservoir So Dead and Brown? A Success Story of Purple Loosestrife Control?” Urban Ecosystem Research Consortium of Portland/Vancouver (11 Mar. 2024), https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/uerc/2024/Presentations/1/

Houck, Michael C. “Anatomy of a Mural: A Seventy Foot Heron Transforms a Lifeless Wall.” The Nature of Cities (23 Jun. 2016), https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2016/06/23/anatomy-of-a-mural-a-70-foot-heron-transforms-a-butt-ugly-wall/

______. Email exchanges, October/November 2025.

———. “Oaks Bottom.” The Oregon Encyclopedia (last updated: 24 May 2022), https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/oaks_bottom/

______. Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge Coordinated Resource Management Plan, Audubon Society of Portland (25 January 1988). https://www.portland.gov/parks/documents/oaks-bottom-wildlife-refuge-resource-management-plan

______. “Preserving Urban Nature, No Silver Bullets.” The Nature of Cities (18 January 2018), https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2018/01/18/preserving-urban-nature-no-silver-bullets/

Houck, Michael C. & M.J. Cody, editors. Wild in the City: A Guide to Portland’s Natural Areas. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2000.

______. Wild in the City: Exploring the Intertwine. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2011.

Jacklet, Ben. “Buying spree brings Metro 7,000 acres.” Portland Tribune (24 August 2001).

Lydersen, Kari. “Trying to Clear the Way.” The Oregonian (29 May 1996).

McKean, Doug. “City Plan Envisions Recreation Uses, Exhibits For New Oaks Pioneer Park.” The Oregonian (8 March 1960).

Meyer, Nancy. “Oaks Park: The Portland Time Forgot.” The Sunday Oregonian (27 March 1994).

Nyden, Evangeline. Memories of Old Sellwood. Portland: Sellwood-Moreland Bee Co., 1960s (rev. ed.).

Peters, Marc. City of Portland Bureau of Environmental Services. Email exchanges, November 2025.

Robbins, William G. Native Cultures and the Coming of Other People. Oregon History Project, 2002, revised 2014. https://www.oregonhistoryproject.org/narratives/this-land-oregon/the-first-peoples/old-world-contagions/

Santner, Darian. City of Portland Bureau of Environmental Services. Email exchanges, November 2025.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “Oaks Bottom Habitat Restoration,” 2018. https://www.nwp.usace.army.mil/environment/oaks-bottom/

“Willamette River.” Wikipedia (last edited 17 October 2025), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willamette_River

Wilson, Mark Griswold. Personal interview, 24 October 2025.

Wilson, Mark Griswold. Email exchanges, November 2025.

Wozniak, Owen. Discovering Portland Parks: A Local’s Guide. Seattle: Mountaineers Books, 2021.

Zachary, K. Joan. Sellwood: Then and Now. Manuscript, early 1970s.